When 95-year-old Jack Balestreri died toward the end of April, The Golden Gate Bridge District declared he had most likely been the last remaining worker to help build the famous span.

When the news drifted to the Central Valley town of Los Banos, 96-year-old Gustavo Villalta turned to his daughter with a bit of bemusement. “He had said to me,” recalled daughter Mary Villalta Brooks, “well I’m not dead.”

True. Gustavo Villalta was very much alive. Indeed, the retired television repairman had his own mini-tale of toiling on the bridge in the mid-1930s.

In 1935, Villalta was a student at San Francisco’s Galileo High School. The Depression had the country in its clutches and Villalta badly wanted cash to go to clubs and hear the orchestras he loved.

One day, as he sat in his class at school, opportunity walked through the door.

“A contractor came around and said they needed a bunch of guys to come over work on some stuff,” Villalta said. The “stuff” turned out to be a job working on the Golden Gate Bridge.

Villalta and a dozen other students bundled up in several layers of coats and turned up at the bridge for work. “He took us to the bridge and to the first tower and there they told us we had to help pulling wire,” Villalta said.

Local

Villalta said the bridge was only just beginning to resemble a bridge. The main cable stretched across the Golden Gate Strait, but the platform was still in its infancy.

By no means was the job glamorous. For three weeks, he earned 75 cents an hour pulling wires for electrical crews installing lights on the first tower. When that was done, he picked up scraps and cleaned-up.

“It was always foggy, recalled Villalta. “I wouldn’t say it was too windy but it was foggy and miserable,” Villalta said at the time.

He never grasped the historical context of the new bridge. He knew it meant he would no longer have to travel through Oakland to get to the dance club he liked in Larkspur. Beyond that, he was far more excited about the creation of Treasure Island which would soon host the World’s Fair.

Even more exciting was the paycheck he got at the end of three weeks.

“All we were thinking about was the money,” he said. “And at that time, 1935 was a critical time for a young boy 16 or 18 years old.”

There were 10 major contractors who worked on the bridge, according to bridge district spokeswoman Mary Currie. Beneath them were dozens of sub-contractors and hundreds of workers.

Work records were scant at the time, and because Social Security wasn’t around yet, there are no lasting records of those employed on the bridge. “That history is all lost,” said Currie.

Villalta’s eyes fill with fire as he leans forward in his chair, wondering aloud why records weren’t kept – why the contributions of so many faded into the churning currents swirling beneath the famous icon.

“He honestly thinks that there’s more people in his position that have worked on the bridge that have just gone undiscovered,” said daughter Villalta Brooks with a grin. Currie said as far as she knows, Villalta is the last living bridge worker, unless someone else comes forward.

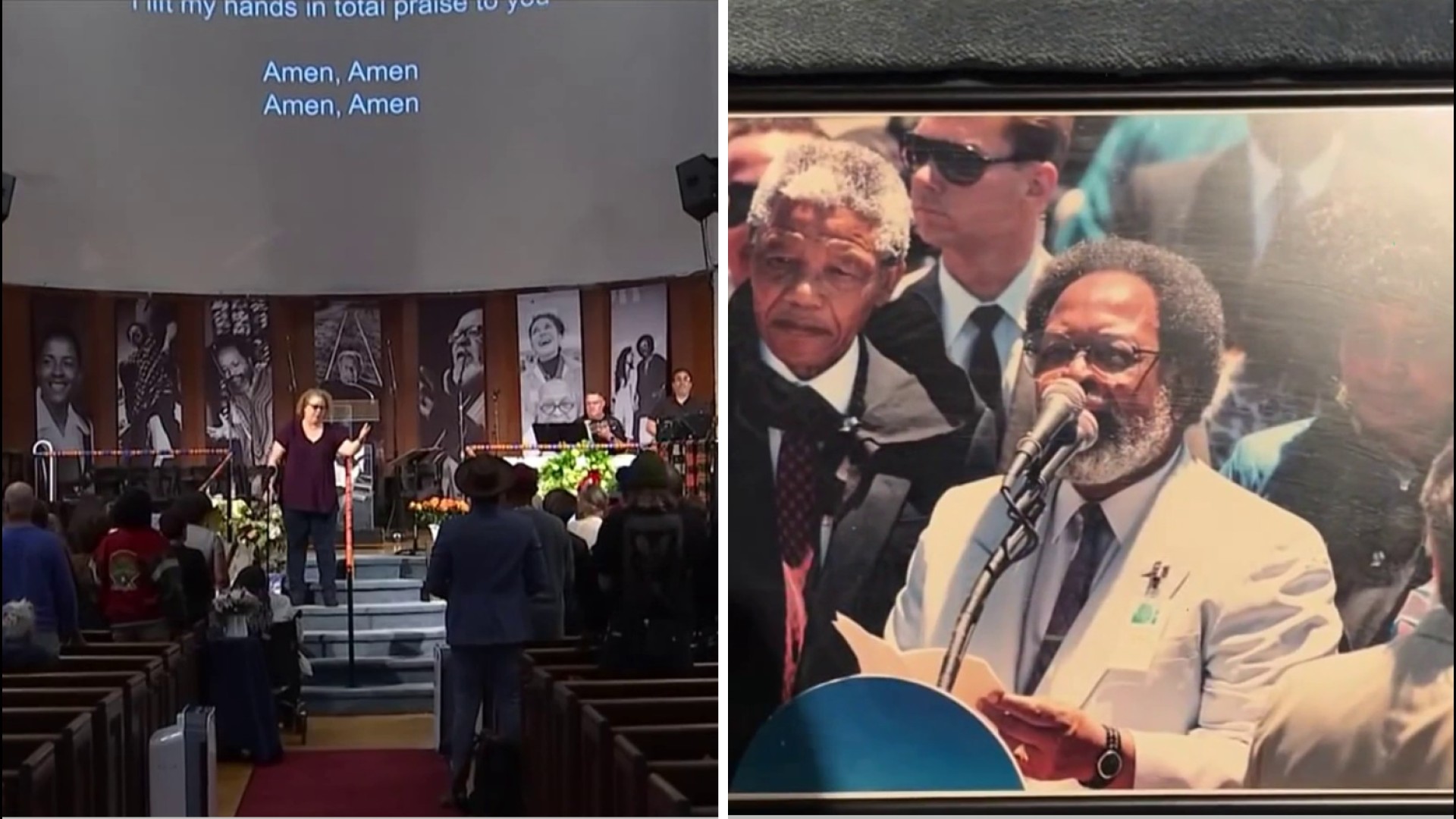

For his small part, Villalta (at rightk, center) downplays his role in building the bridge. He reacted with embarrassment and shock when an NBC crew showed up to interview him at his assisted-living facility in Los Banos.

He shuddered with horror when it was suggested he had played a role in the bridge’s history. He hardly had anything to do with it, he insisted.

But Villalta lit up as he rattled off the joints he and his friends would prowl as a young men growing up in San Francisco – Sweet’s Ballroom; The Fox Theater; the Treasure Island World’s Fair.

And a knowing smile crept across his face when asked if he remembered how he spent his paycheck for his bridge work. “I spent it on girls,” he said. “What else can you spend it on?”