It's possible to drive through Marin City without ever knowing you're in Marin City. Felecia Gaston would like that to change.

To Gaston, the issue isn't so much what there is to see in this unincorporated city of 3,000 – overshadowed by adjacent Sausalito and Mill Valley – it's more about what there is to know.

"It’s not just the place but the people who have survived for all of these eight generations," Gaston said.

This year, Marin City is marking 80 years since it was born as labor housing for workers who flooded the area in 1942 to build military ships in the nearby Marinship operation on Sausalito's bay front. The area swelled with life as thousands of Blacks left the segregationist South for jobs in the shipyard, helping to turn out some 90 Liberty Ships and tankers in just several years.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

But Gaston believes time has turned its back on that chapter of Marin City's history – the plight of African Americans who were left stranded without jobs or opportunities when the war ended and the shipyards closed in 1945. That's a story Gaston has committed to telling.

Inside an upstairs room in the office of Performing Stars, a youth activity program Gaston founded in Marin City 30 years ago, she's quietly socked away articles and memorabilia detailing Marin City's history. Shelves are stacked with thick binders detailing the town's past. From the chaos of the room, Gaston produced a worn suitcase once owned by Annie Small, a Louisiana native who came by rail to work in the shipyards.

"She talked about how the train was so crowded coming to California that she sat on her suitcase," Gaston said, admiring the case. "All the way from Shreveport, Louisiana, to California."

In Marin County, where the median home price is over a million dollars, Marin City struggles under institutional poverty leftover from the demise of the shipyards, along with discriminatory housing policies of the era that made it nearly impossible for Black workers to buy homes like their white co-workers.

"The Blacks were not able to purchase homes because of the red lining," Gaston said, referring to racially-charged real estate practices that denied home loans to Blacks.

Having grown up in Marietta, Georgia, Gaston was well acquainted with the evils of segregation. As a child, she was denied the opportunity to take ballet lessons, which were only afforded to white children. It was the inspiration behind her creating the Performing Stars program which offered economically-challenged kids in Marin County the chance to take classes in ballet, theater and music. In the last three decades, the program has served more than 3,000 children.

It's the same compulsion that has inspired Gaston to launch an all-out blitz to draw attention to Marin City's 80th anniversary, which includes an art installation, a musical theater play about Marin City performed by the Marinovators, and a history exhibit in the Marin County Civic Center opening in August.

"Through our archives, people are really going to get to know who the residents were and who they are and the fact that we have a legacy," Gaston said.

Gaston decries the fact that punching Marin City into a phone's GPS will only yield results for nearby Sausalito or that a Google search will sometimes turn up articles describing Marin City as the "ghetto of Marin." She said that anyone who points out that Marin City has no main street or downtown is missing the point.

"Even though the Black population has dwindled, we’re able to still be able to share this rich history of what the Black community has gone through," she said.

Her endless preaching about Marin City has helped inspire a pride-of-place among the young people who live in the area and now have a history to boast about.

"I learned to love my city because of people like Miss Felecia, who's working hard to make the community look beautiful," said Antanasia Cook, a resident who's involved in Gaston's youth programs.

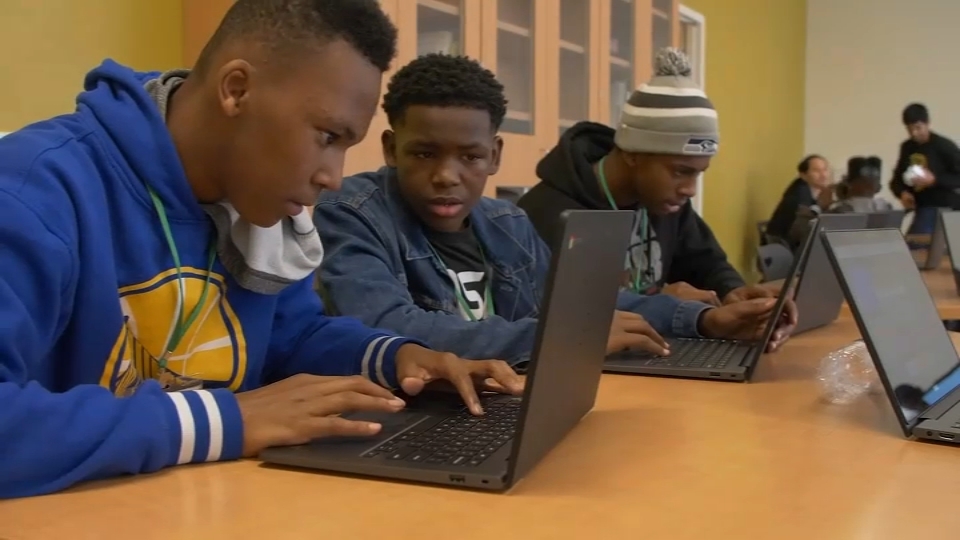

As part of the anniversary festivities, Gaston's group transformed a storefront in a nearby mall into a temporary history center. Windows were painted with the images of some of Marin City's pioneers who worked in the shipyards, like suitcase-riding Annie Smalls or Joseph James, a singing welder who successfully challenged the discriminatory practices of the shipyard's union. Inside the building, students created a virtual reality exhibit to give a glimpse into the area's story.

"Eight generations of Black folks have lived in this community and neighborhood," said Jahi Torman, an activist and musician who has worked alongside Gaston. "Felecia is one of those great warriors who can assemble all of these artifacts and history and preserve it for the future generations."

Gaston has the energy of a comet, fielding constant phone calls and organizing along multiple activity fronts, including distributing PPE masks, COVID-19 testing kits and diapers from the office of Performing Stars.

She bristles when she hears negative depictions of her town, blaming it on a lack of understanding. There is much history here, she maintains, both good and bad. You only have to scratch for it.

"You think about Marin City and you actually don't even know unless you just happen to come here," Gaston said. "You have to come here to experience Marin City."