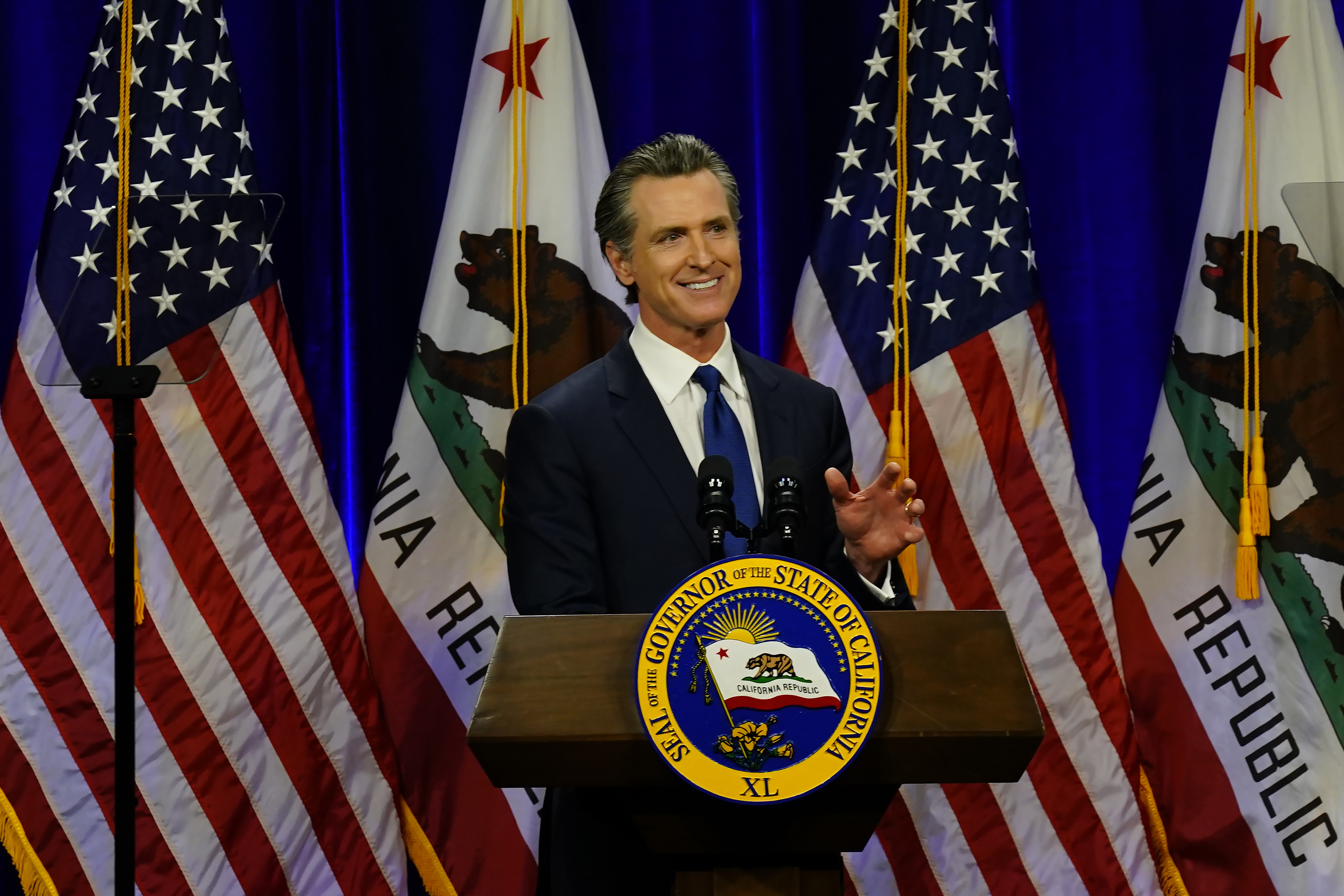

California lawmakers on Monday passed a $300 billion operating budget over the objections of Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, highlighting disagreements among Democrats about how to spend a record-breaking surplus that, by itself, is more than most other states spend in a year.

While Newsom does not support the Legislature’s spending plan, lawmakers sent the bill to his desk anyway because the California Constitution requires them to pass a budget by Wednesday or else they don’t get paid. Unlike most states, California lawmakers are full-time and get paid $119,702 per year.

Newsom and legislative leaders will continue negotiating with the goal of coming up with a spending plan they can all agree on before the start of the fiscal year on July 1.

The Democratic-controlled Legislature wants to spend more money than Newsom does on education and housing. The lawmakers’ plan would cover college tuition for 150,000 more students than Newsom would.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

And lawmakers want to borrow about $1 billion per year and use it to help about 8,000 first-time buyers purchase a home by covering 20% of the price. The plan could potentially lower mortgage payments by about $1,000 per month in a state where the median home price hit a record high of $849,080 in March.

“This is the budget that you ran for office for,” Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, a Democrat from Sacramento, said Monday while urging lawmakers to vote for the bill.

Lawmakers say they can afford to do those things because California’s revenues have soared throughout the pandemic as the rich have gotten richer and pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes compared to other states. This year, California’s surplus — money left over once the state has fulfilled its existing commitments — is more than $97 billion.

But Newsom doesn’t like the Legislature’s plan because he says it would spend too much of the state’s surplus — money that is only available for one year — on things that must have more than one year of funding, mostly for schools and community colleges. The Legislature’s plan would spend $2.4 billion more for ongoing expenses than Newsom’s plan, a disparity that would grow to $5.6 billion by 2026.

While California has lots of money today, the Newsom administration fears the economy is showing signs of stress as stock prices fall and inflation keeps going up because of supply chain disruptions and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“Given the financial storm clouds on the horizon, a final budget must be fiscally responsible,” said Anthony York, Newsom’s senior advisor for communications. “The Governor remains opposed to massive ongoing spending, and wants a budget that pays down more of the state’s long-term debts and puts more money into state reserves.”

Lawmakers disagree. They say the extra money they want to spend is small, accounting for less than 1% of total spending. Plus, legislative leaders noted Monday that their plan includes “record-high reserves” — about $700 million more than Newsom proposed — “to protect California during future economic slowdowns.”

This type of disagreement is typical in California, where governors usually see their role as stopping the progressive Legislature from spending too much money.

But Newsom’s plan has its own problems. It would leave the state about $25 billion over a constitutional limit on spending over the next two years, a situation the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office says could push the state over a “fiscal cliff” that could force budget cuts even if state revenues continue to grow.

The Newsom administration has downplayed those concerns, noting their plan would spend 95% of the budget surplus on one-time expenses — money that could be pulled back in an emergency.

One thing Newsom and legislative leaders can agree on is they want to give a portion of the budget surplus back to taxpayers to help them pay for record-high gas prices. But they can’t agree who should get the money, and how much they should get.

Newsom wants to send checks of up to $800 to everyone who has a car registered in the state. The Legislature wants to send $200 checks to people who have taxable income below a certain level — $125,000 for single people and $250,000 for couples.

Newsom’s plan would cost $11.5 billion and taxpayers might get the checks a little faster because the money would come on a debit card. The Legislature’s plan would cost $8 billion, but it wouldn’t benefit the wealthy.

“We should be supporting those families and households, middle class and below, that would be really struggling from these costs versus those with incomes for whom this would not be as much of a problem,” said state Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Democrat from Berkeley and chair of the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee.

Republicans don’t like either plan. Instead, they favor a suspension of the state’s gas tax, which at 51.1 cents-per-gallon is the second highest in the nation.

“There’s nothing in today’s proposal to bring immediate relief for Californians, said Assemblymember Vince Fong, a Republican from Bakersfield and vice chair of the Assembly Budget Committee. “As the state coffers grow, family bank accounts are shrinking and Californians consistently pay more and more to Sacramento and get pennies back temporarily. That is not relief.”

___

This story has been updated to correct that Assemblymember Vince Fong is from Bakersfield, not Fresno.