It happened with devastating speed in Fukushima, Japan.

It’s happening slowly all over the United States: radioactive waste is seeping into the soil and groundwater.

As she paces the fence at Lawrence Livermore Labs near her home, Marylia Kelley shakes her head about a new Environmental Protection Agency proposal that could affect communities like hers if a future radioactive release were to occur. It’s called a Protective Action Guide, or PAG. If formally adopted, it would set new, much higher levels on radioactive materials to be allowed in drinking water supplies following any kind of “radiological” accident or spill for an undetermined “intermediate” period of time.

Neighborhoods around Livermore labs already have radioactive uranium and tritium in the groundwater - a byproduct of the lab’s research on nuclear weapons. It’s been on the Superfund list for decades. As Executive Director of Tri-Valley Cares, a community watchdog group that monitors Lawrence Livermore Lab, Kelley has been keeping tabs on all the contaminants that show up in the groundwater.

“The current state of understanding of radioactive pollution is that there is no safe level of radiation exposure,” says Kelley. “ She adds that, “Ironically, it was a researcher here at Livermore Lab who first promulgated and then over time proved that hypothesis.”

That researcher was John Gofman, a medical doctor and nuclear physicist. In his book, Nuclear Witnesses, Insiders Speak Out, Gofman wrote, “It is not a question any more: radiation produces cancer, and the evidence is good all the way down to the lowest doses."

Local

Kelley worries about what the new EPA PAG plan will do to her community. “The health of the workers and the health of my community and my family are literally put at risk when you make cleanup standards more lax,” Kelley says.

It’s not just communities like Livermore that are at risk. Radioactive contaminants are all around us - in university research labs, hospitals, and factories. UC Davis has plutonium buried on site. General Electric left radioactive material near Sunol after operating four nuclear reactors there. There have been repeated findings of radium on Treasure Island.

Radioactive materials are transported worldwide on roads, railways and ships. According to the World Nuclear Association, there are some 20 million shipments every year.

Despite repeated requests, the EPA would not speak with NBC Bay Area about the new guidelines. The agency did offer this statement:

During a radiological emergency, radioactive material could be released into the rivers, lakes, and streams used by public water suppliers. Using the best available research, EPA will release, for the first time, non-regulatory guidance that authorities can use to protect residents from experiencing the harmful effects from radiation in drinking water following a nationally significant radiological emergency. EPA anticipates the release of the non-regulatory guidance by the end of the calendar year.

At the University of Santa Cruz, Daniel Hirsch is astounded when he looks at the new plan.

“I understand why they’re trying to do it quietly, but it’s something completely outside of what their job is,” says Hirsch, “They’re supposed to protect us, not harm us.”

Hirsch teaches Environmental and Nuclear Policy to graduate students at the UC Santa Cruz. “When I looked at the table of numbers that they were proposing and compared them to the Safe Drinking Water levels, I almost fell off my chair. What the EPA proposal is doing is allowing you to drink, in a single glass of water, as much radioactivity as you would normally be allowed in an entire life time,” he says.

The Safe Drinking Water Act sets Maximum Contaminant Levels, or MCLs. The table below shows those limits for radioactive contaminants, known as radionuclides.

(You don’t need to understand the units of measure to follow this, but here’s an explanation from the Army Corps of Engineers.)

When contaminant levels exceed the limits, officials “take action” such as provide bottled water to a community or evacuate residents.

The Safe Drinking Water Act was designed so that not more than one in a million people would get cancer by drinking water over the course of a year. According to Hirsch, these new levels increase that risk by at least a thousand times. In some cases, he warns, “the EPA proposal is allowing you to drink, in a single glass of water, as much radioactivity as you would normally be allowed in an entire lifetime.”

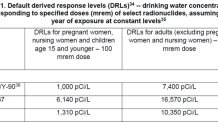

The table below shows EPAs proposed limits following a nuclear accident. There are different numbers for pregnant women, nursing women and children. Compared to the Safe Drinking Water Act, the level for strontium-90 is almost 1,000 times higher, for Iodine-131, almost 3,500 times higher.

For full text of various PAGs proposed by EPA, click these links:

Strontium-90 is known as a “bone-seeker.” According to the Oakridge National Laboratory, when dogs were given a single inhalation of Strontium-90, “those dogs that survived past two years had an excess of bone tumors.”

As for Iodine-131, this article from Harvard’s Medical School shows how the human thyroid gland mistakes it for regular Iodine, allowing the radioactive version to wreak havoc on DNA.c

The opposition to the EPA plan is growing. It currently includes 60 environmental groups, Senator Barbara Boxer, and Asst. New York Attorney General John Sipos. When the EPA posted its plan for public review, comments opposed to the measure were more than 62,000. In favor: about six.

Jeff Ruch is a member of one of the 60 groups that has expressed opposition to the plan, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER). PEER intends to sue the EPA. He says what happened in Flint is nothing compared to what could happen under the new EPA guidelines. “To put it in perspective - in Flint where we had lead exposure in the water it was one and a half times that of safe drinking water level. Here they're talking about hundreds and thousands of times the exposure for a much greater period of time without a guarantee. And what we're concerned about is that they may finalize this guidance before the American people have any idea what's going on.”

Dr. Jerrold Bushberg, a Radiation Biologist at UC Davis Medical Center, agrees that there’s certainly a big numerical difference between the new proposal and the Safe Drinking Water Act. But, he says, “I think a lot of the confusion comes from the intent for which these two standards will be used.”

Dr. Bushberg says that the new action levels would be used “following some sort of event - could be a dirty bomb or it could be released from some other source - in which you would take protective actions. That could be everything from evacuation to going on to bottled water to restricting intake of food and vegetables. These are for a relatively short period of time.”

The Investigative Unit reached out to scientists at dozens of universities across the country.

Dr. Doug Brugge, a biologist and industrial hygienist at Tufts University said,” I would suggest that calculations of that risk be attempted and provided before moving forward with the new guidance. And I would also be concerned about applying the PAGS to a period that extends up to years after the emergency. Some leeway in an emergency makes sense.”

Dr. Clair Sullivan, a nuclear engineer and physicist at the University of Illinois, says, “It is my opinion that the PAG is guidance for an accident scenario, which is a one-time event, whereas the SDWA is for our day-to-day lives and is federal law. The PAG does not imply that the country is allowed to increase the radiation contaminants in water by several orders of magnitude as a daily occurrence.”

The only clear verdict from the scientists we surveyed was that the EPA documents were complex and difficult to navigate, even for scientists with PhD’s.

It also seems clear that not everyone at the EPA is in agreement over the new proposal.

NBC’s Investigative Unit obtained internal documents in which the EPA’s own experts and lawyers question the new plan, and how it might undermine the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Stuart Walker, the EPA’s National Radiation Expert, writes, “the concentration numbers seemed high…I noticed that a number of the PAG concentrations are thousands of times higher than the MCL’s…I used MCLs since these are measures the EPA uses when making decisions about bottled water during emergencies involving class A carcinogens.” (see full text of internal emails here)

Charles Openchowski, senior attorney in the Office of General Counsel at the EPA, writes, “this guidance would allow cleanup levels that exceed MCLs (maximum contamination levels under the Safe Drinking Water Act) by a factor of 100, 1,000, and in two instances 7 million, and there is nothing to prevent those levels from being the final cleanup achieved.”

In another email, Stuart Walker writes, “It also appears that drinking water at the PAG concentrations...may lead to sub-chronic (acute) effects following exposures of a day or a week.”

In light of all the controversy, why won’t the EPA sit down with the Investigative Unit and explain what the agency is doing and why?

Daniel Hirsch has his own explanation. “It’s expensive for industry to control these releases, it’s expensive to clean them up when there are releases, it’s expensive for the Department of Energy or the Navy or other Department of Defense facilities that have been contaminated to clean up. So it’s easier to lean on your friends within the EPA and say you don’t have to control these releases, you don’t have to clean them up, and so what that means is the agency or industry saves some money, but members of the public end up with cancers, leukemia and genetic effects.”