In an effort to stop the torrent of disability lawsuits against small businesses, the district attorneys of San Francisco and Los Angeles are suing a law firm for bringing what the prosecutors claim are unlawful and fraudulent lawsuits under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The lawsuit, filed April 11, comes after a staggering increase in ADA lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

An analysis by Bay City News shows that ADA lawsuits in the district leapt from 873 in 2020 to 2,463 in 2021, a nearly threefold increase.

To put that in context, the total number of civil cases filed in the district in 2021 -- everything from free speech cases to antitrust and securities class actions to billion-dollar intellectual property suits to mass tort litigation -- amounted to just more than 9,000 cases.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

ADA litigation in 2021, at least as measured by new filings, constituted more than 25 percent of the court's docket.

Just 10 plaintiffs filed 85 percent of those cases, and they were all represented by Potter Handy LLP.

The suit in San Francisco Superior Court accuses the San Diego law firm Potter Handy and 15 of its lawyers of violating California's unfair competition law.

The filing -- a 58-page complaint with more than 300 pages of exhibits, including court filings, transcripts and photographs, alleges a plan by the lawyers to end-run California legislation that was enacted to discourage serial ADA lawsuits by what the state Legislature termed "high frequency litigants."

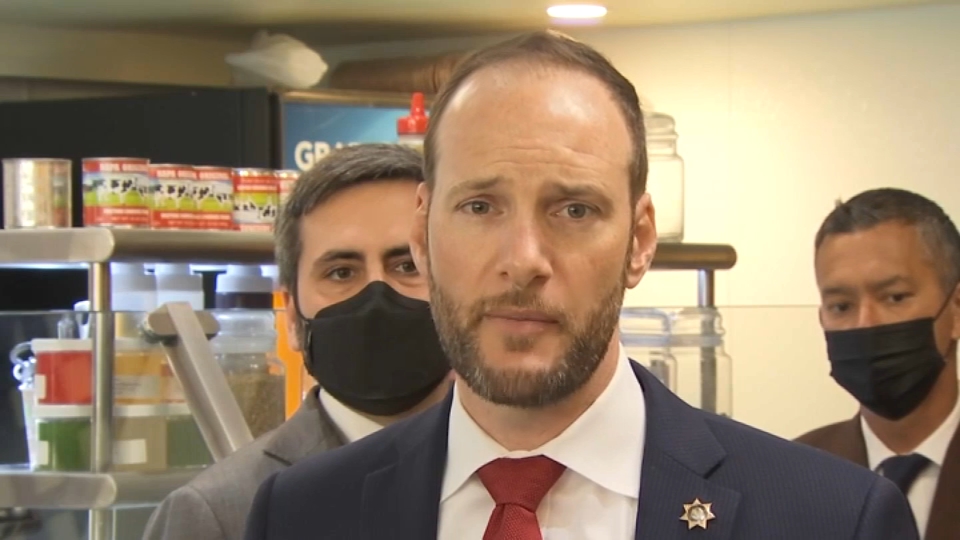

The filing by San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin and Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascon alleges that the firm and its clients "schemed" to avoid the state court rules by bringing their new cases in federal court where the state rules did not apply. The problem with the plan, according to the prosecutors, was that litigants in federal court can only bring suit when their clients have proper legal "standing."

Standing is the term used to describe what a plaintiff must prove to show that he or she is entitled to litigate his or her claim in federal court. Without legal standing, a federal judge has no jurisdiction and must dismiss the case.

The district attorneys allege that many -- perhaps most -- of Potter Handy's clients did not have standing, and that even though the firm allegedly knew that, they still filed the cases.

The district attorneys are requesting that the court prohibit the law firm from further violations of California's unfair competition law. The filing also asks the law firm to repay thousands of small businesses the monies they paid to settle claims brought over the last four years.

The suit also seeks statutory damages that could amount to millions of dollars.

A Potter Handy attorney defended the firm's practices and accused the district attorneys of bringing the case for political reasons as they both face threats of a recall.

Potter Handy

The district attorneys' lawsuit alleges that Potter Handy brands itself as a "Center for Disability Access" when it asserts an ADA claim "to mislead businesses and the public into believing Potter Handy is a legitimate disability rights advocacy group when it is in fact a for-profit law firm."

Potter Handy's complaints show a typical pattern. A lawsuit is filed against a store or a restaurant or a hotel. The filing comes without prior notice or demand. The complaint says that the plaintiff has a disability and visited the defendant's place of business but encountered "unlawful barriers" to access.

The barriers encountered can be physical or design features that create challenges for equal access such as door handles that are too hard to grasp or pull, counters that are too high, pathways that are too narrow for wheelchairs, handicapped parking slots not adequately marked, and doorways that lack ramps.

The complaint then asserts a claim under the ADA for the accessibility barrier. The plaintiff also adds a claim under California's Unruh Act, a state law that in this context makes a violation of the ADA a violation of the Unruh Act. Unlike the ADA, which only provides injunctive relief, the Unruh Act provides for statutory damages of $4,000 per visit.

Potter Hardy's plaintiffs typically ask for an injunction to remedy the problem, statutory damages, and attorney fees and other costs of litigation.

Many of the cases settle quickly. Of the 578 cases Potter Handy filed in the district in July, August and September of 2021, more than half had been resolved by March 1.

Of the resolved cases, the average time from filing the complaint to dismissal was 105 days, quick by the standards of most federal court cases.

Settlements are not filed publicly, and each case has different factors that influence the settlement amount, among them the type of violation and the defendant's ability to contest it.

San Jose attorney John McIntyre has represented defendants in 10 ADA cases, half brought by the Potter Handy firm.

Based on his experience, McIntyre said, "the usual demand from the plaintiffs is somewhere in the $18,000 to $20,000 range. And my experience is I can usually get them down to somewhere between $7,500 and $10,000."

McIntyre said, "I feel like I need to apologize to people for being a lawyer when I see cases like this … when members of my profession file what I believe to be predatory lawsuits against small business for very minor infractions of questionable and obscure building code requirements because the law permits recovery of automatic statutory damages and attorney fees."

The district attorneys' suit evidences a similar perspective. According to the court filing, Potter Handy has turned the purposes of the ADA into a financial bonanza.

"Potter Handy uses ADA/Unruh lawsuits to shake down hundreds or even thousands of small businesses to pay it cash settlements, regardless of whether the businesses actually violate the ADA," the suit says.

The filing alleges that "Potter Handy's boilerplate lawsuits are not clever lawyering that happened to find a hole in a well-intentioned statute. They are able to evade California's procedural reforms only because they rely on false standing allegations, and their lawsuits are therefore unlawful under current law."

The End-Run

The DA's lawsuit focuses on the interplay between the ADA and the statutory damages provided in California's Unruh Act. Because the Unruh claim is a fixed amount with no need to prove economic injury, it is a valuable bargaining chip in settlement negotiations. McIntyre says that it is "always the big hammer that's held over the defendants."

In December 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit decided an ADA appeal in the Los Angeles case Arroyo v. Rosas that involved the question of whether it was appropriate for the lower court to exercise its jurisdiction over the Unruh claim. Potter Handy was counsel for Arroyo.

The defendant in that case pointed out that the California Legislature, unhappy with "what it perceived to be abuse of the Unruh Act by 'a very small number of plaintiffs' attorneys," amended the Act in 2012 to require high frequency litigants to explain in their complaint the "specific access barriers" and how they denied the plaintiff full and equal access.

In 2015, the Legislature amended that statute again, this time "in order to address what it believed was continued abuse by high frequency litigants."

These lawsuits frequently targeted "small businesses on the basis of boilerplate complaints" to pursue "quick cash settlements rather than correction of the accessibility violation."

Under the 2015 amendments, a high-frequency litigant has to disclose in its court filing, among other things, "the reason the plaintiff was in 'the geographic area of the defendant's business'; and why the plaintiff 'desired to access the defendant's business.' "

The Legislature also imposed an additional court filing fee of $1,000 for each filing by a high-frequency litigant.

The Arroyo court explained that some litigants had figured out how to end-run the state law rules.

Because the $1,000 filing fee and the changed pleading rules only apply to cases filed in state court, an ADA plaintiff could simply file a complaint in federal court and add the state claims under the federal court's "supplemental jurisdiction" over related state law claims.

"In short," the court said, "the procedural strictures that California put in place have been rendered largely toothless, because they can now be readily evaded."

The court summed it up: "The consequences of these various laws, taken together, was to make it very unattractive to file such Unruh Act suits in state court but very attractive to file them in federal court."

It wasn't surprising, the appeals court said, that ADA filings in the Central District of California, where Los Angeles is located, jumped from 419 in 2013 to 3,374 in 2019.

Legal Standing

The district attorneys' lawsuit is based on the idea that in order to end-run the state court rules, Potter Handy had to get over the requirement that plaintiffs in federal court must have standing to file the lawsuit. The prosecutors allege that Potter Handy's clients did not.

A case currently pending in a San Francisco federal court provides insight into the dispute about standing.

The case, Whitaker v. Slainte Bars LLC, was filed on May 19, 2021, and assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Jacqueline Scott Corley of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.

Brian Whitaker alleged that in May 2021, he went to the Alhambra Irish House, a restaurant in Redwood City owned by the defendant. He went "with the intention to avail himself of its goods or services," but he encountered barriers to access in the form of outdoor "dining surfaces" not accessible for wheelchair users.

There was a lack of "sufficient knee or toe clearance under outside dining surfaces" and also outside tables that were "too high."

These barriers created "difficulty and discomfort" for Whitaker.

Whitaker said that he will return to the restaurant when he is told that it is accessible. In the meantime, however, he alleged that he was deterred from doing so.

The allegation that Whitaker intended to return to the Alhambra Irish House was of crucial importance to his claim that he had standing.

In order for an ADA plaintiff to have standing to seek an injunction, he or she must not only demonstrate that he or she has been injured by actions of the defendant but also that there is a real and immediate risk that he or she will suffer harm in the future if the injunction is not issued.

As a 2011 decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit put it, a plaintiff "lacks standing if he is indifferent to returning to the store or if his alleged intent to return is not genuine."

Ara Sahelian, the lawyer for the defendant, asserted that Whitaker had no genuine intent to return to the restaurant.

The court convened an evidentiary hearing and the parties presented evidence and filed briefs in support of their positions.

Sahelian produced evidence that Whitaker lives in Los Angeles, four and half hours by car from the Alhambra Irish House.

Sahelian also asserted that Whitaker has never returned to any of the 1,733 establishments that he has sued in the past and has no concrete plans to do so.

Sahelian asserted that Whitaker could not identify any single business he returned to, and he had no list or records of any return visits, and alleged that if Whitaker actually tried to go back to all the places that he sued, it would be a multi-year undertaking.

Those alleged facts, together with the asserted implausibility of some of Whitaker's other contentions -- for example, that he comes twice a month to the Bay Area not primarily to file lawsuits but because he is considering moving there -- demonstrated, Sahelian argued, that he does not actually intend to return to the Alhambra Irish House in Redwood City and therefore the court should dismiss the case for lack of jurisdiction.

Whitaker's lawyer, Dennis Price, accused Sahelian of mounting an attack on "the victim of discrimination." He pointed out that the ADA is a civil rights statute and courts have traditionally shown flexibility on standing for civil rights plaintiffs.

Price said that "Mr. Whitaker factually has returned to numerous, countless businesses that he has sued. He is not obligated to keep receipts of these return visits or document them for the curiosity of future litigation."

The case is currently awaiting decision.

Clashing Perspectives

Price is a partner in Potter Hardy and a named defendant in the district attorneys' suit. He directs litigation strategy in the firm's ADA cases.

In an interview with Bay City News, Price discussed his firm's ADA litigation practice and expressed pride in the firm's work.

He said that the firm has a couple of dozen attorneys working on ADA matters. "We're not a large firm in the scope of what the legal world might consider a large firm, but we are bigger than people realize."

He said "every one of our cases has a confirmed violation of the ADA." In every case, one of the firm's clients had actually experienced the barrier to access and if it involved something that requires measurement -- the height of a table or width of a parking space -- an investigator hired by the firm had gone out to confirm.

Price said that Congress intended the ADA to be enforced by individuals acting as "private attorneys general," thereby saving taxpayers the cost of hiring armies of paid bureaucrats to enforce the statute.

The act was passed under the administration of George H.W. Bush at a time when new taxes were unpopular, so no agency was created to enforce the ADA. That work was left to private individuals.

Price says that his clients' lawsuits correct violations of law that have been around for years and would otherwise persist for years into the future. The ADA was enacted in 1990 and if the owners of stores and restaurants have not yet figured out that they are required to comply with the statute, lawsuits are the only thing that will work.

Price recognizes that "there's a lot of very, very bad press that gets written on these types of cases."

But he thinks it is terribly unfair that the burden of enforcing the law is "being put entirely on people with disabilities … and then they're being vilified for doing that." The firm doesn't "bring claims based on insignificant violations. They're only insignificant generally through the scope of somebody who doesn't really understand why these issues are what they are," Price said.

Sahelian has a personal perspective on the litigation because he uses a wheelchair as a result of childhood polio. "I'm keenly aware of every aspect of accessibility."

After reviewing the district attorneys' suit, he commented that the Potter Handy firm has "taken what was meant to be a noble act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and perverted it to yield phenomenal amounts in cash, without accountability."

He says that Potter Hardy never backs down. "Their downfall is that they play scorched earth. They will fight every step of the way."

Price, after the announcement of the lawsuit, came out swinging. He accused the district attorneys of bringing the case for political reasons.

"Both DAs are facing serious recall threats for the perception of not faithfully executing the duties of their offices and are filing these claims in order to generate support," he said.

Price went on to say, "Our clients' cases make California significantly more compliant and are doing what the state of California and the U.S. Congress anticipated would need to be done to enforce the ADA. There is no dispute that the businesses that have been subject to our claims violated the law. Instead, the fingers are being pointed at our clients, the victims, for noticing."