How easily a stolen gun can be matched to one used in a crime depends on laws that can either speed or impede the trace.

Making the job easier: mandatory reporting of lost or stolen guns and background checks, measures opposed by the National Rifle Association and other gun rights groups but favored by gun control organizations. But these regulations are limited because although federal laws govern licensed gun dealers, they do not apply to private individuals and the majority of states have not extended their laws to close the gap.

Making it more difficult: the federal Tiahrt Amendments and the Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986, which impede the dissemination of records to researchers or others outside of law enforcement or forbid the creation of a registry of guns, gun owners or gun sales.

William Rosen, the deputy legal director of Everytown for Gun Safety, accused the gun lobby of stoking fears that the government would use a registry for a mass seizure of guns.

"Despite the fact that that’s quite a paranoid belief and it’s unclear how something like would ever even possibly unfold," Rosen said. "So clearly not a realistic fear, but it has been something that the gun lobby has used very successfully to basically oppose any measures no matter how seemingly reasonable to reduce gun violence."

Michael Hammond, the legal counsel for Gun Owners of America, said such fears are warranted. He pointed to comments that New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo made when the state was considering new restrictions on assault weapons after the rampage at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. In 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza shot 20 kids, ages 6 and 7, to death and six of the school's staff.

"Confiscation could be an option," Cuomo said in an interview on an Albany, New York, radio station in 2012. "Mandatory sale to the state could be an option. Permitting could be an option — keep your gun but permit it."

U.S. & World

In the end, New Yorkers were allowed to keep assault weapons they possessed legally on Jan. 15, 2013, but had to register them by Jan. 15, 2014. And the courts upheld the constitutionality of the law.

To try to determine where stolen guns end up, more than a dozen NBC stations across the country teamed up with the nonprofit journalism organization The Trace. To get around legal prohibitions against sharing national data with the public, The Trace and NBC obtained records from more than 1,000 law enforcement agencies in 36 states and Washington, D.C., and identified more 23,000 stolen guns recovered by police between 2010 and 2016, most connected with crimes. Those included more than 1,500 violent crimes such as murders, sexual assaults, armed robberies and kidnappings.

One gun stolen in 2010 was used two years later to kill Rory Park-Pettiford, a 22-year-old Campbell, California, man, who was shot to death during an attempted carjacking.

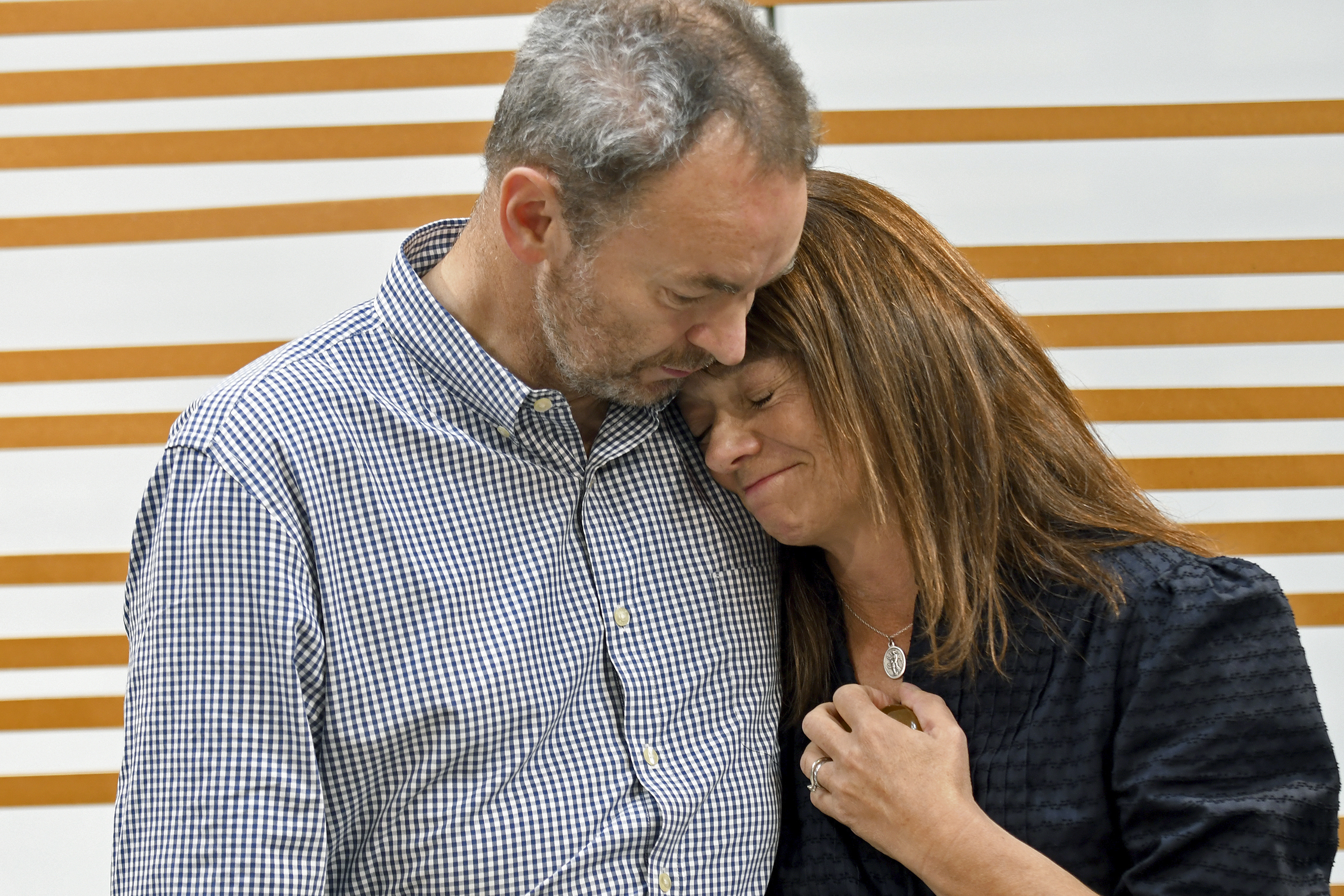

His brother, Dylan, a writer and director and a veteran of the U.S. Air Force, said of the killing: "Rory's death caught me more off guard than any road side bomb in Iraq ever could. You just don’t expect for something like that to happen, especially in a place where we grew up."

During the trial, he recalled, he watched security footage showing a man walk up to his brother's car and shoot him through the driver’s side window.

"And I watched my brother take his last breath," Dylan Park-Pettiford told NBC. "That’s something that replays in my mind all the time."

Tightening of federal laws has occurred infrequently. In the last 50 years, the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 and the Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibited some sales and set new licensing and record-keeping requirements for dealers. The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 mandated background checks and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 banned the manufacture of new semi-automatic assault weapons for 10 years and large-capacity ammunition magazines. The assault weapon ban was allowed to lapse in 2004.

Some states have toughened their local laws, but those remain a minority and the upshot is hurdles for law enforcement, researchers and others investigating gun violence in the country.

Mandatory reporting laws hold people accountable, and can be effective in reducing gun trafficking, gun control advocates say. Reporting requirements allow law enforcement to see if there is a pattern of thefts in a particular neighborhood and and try to determine what happened to the guns before they are used in a crime, Rosen of Everytown said.

"But another benefit of those laws is they take away an excuse from someone who is straw-purchasing guns, who is diverting guns from the legal market to the illegal market," he said.

A straw purchase involves a buyer purchasing a gun for someone else who cannot pass a background check and is legally barred from owning a weapon.

Without mandatory reporting requirements, police officers and others can quickly run into road blocks, advocates say.

"If there is no reporting requirement, they have no leverage to say, 'This is your gun and it was used in a crime and you have to explain it,'" said Lindsay Nichols, the federal policy director at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. "And if there is no reporting requirement, the person says, 'No I don’t have to explain.' That is a very important requirement."

Federally licensed firearms dealers must report the loss or theft of weapons from their inventory. The vast majority of states impose no local requirements, though nine state and the District of Columbia do also make individuals report lost or stolen firearms: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio and Rhode Island, according to the Giffords Law Center. In Maryland, owners must report the theft of handguns and assault weapons but not other firearms. In Michigan, individuals have to notify law enforcement about thefts but not losses.

The NRA told NBC that it opposes mandatory reporting of lost and stolen guns. Such laws do not prevent crimes from being committed, it said. The National Shooting Sports Foundation says the focus should be on criminals, not on penalizing gun owners who fail to report thefts.

Hammond also said the requirement was an unreasonable imposition on anyone with a large inventory of guns.

"If you're a huge gun dealer, basically having an affirmative obligation to survey your inventory and know what guns you have on any given day at the expense of going to prison is something which is a pretty much a trap," he said.

Background checks can not only keep guns out of the hands of people who are prohibited from owning them but they create a record of who owns a gun.

Federally licensed firearms dealers must perform background checks, keep records of all gun sales and report some multiple sales. But none of the requirements apply to private or unlicensed sellers.

Again most states have not extended checks to apply to individuals although 19 states have imposed obligations on at least some private sales, according to the Giffords Law Center. Nine states, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington plus the District of Columbia require background checks for all sales, including those from unlicensed sellers. Maryland and Pennsylvania do so for handgun purchasers only.

In addition, four states, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts and New Jersey, require all purchasers to get a permit after a background check. Another four, Iowa, Michigan, Nebraska and North Carolina, apply the requirement to only handgun purchasers.

"In a state that doesn’t require background checks on all gun sales, the trail may go cold (after the first purchase) even though that gun may have been bought and sold any number of times after that initial purchase," Rosen said.

Without the checks, even law enforcement officials can be stymied in trying to trace a gun's path, gun control advocates say.

"So those two laws could work powerfully in tandem, background checks and lost and stolen reporting, to again to make sure we understand the chain of custody," Rosen said.

The NRA says it opposes expanded background checks because they do not stop criminals from getting firearms, and because it opposes firearm registration.

Meanwhile, other laws add to the difficulty of matching guns and crimes, gun control advocates say.

The Tiahrt Amendments, named for former U.S. Rep. Todd Tiahrt, a Republican from Kansas, prohibit the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms from releasing data on gun traces for use by cities or states, researchers, those involved in lawsuits or other members of the public.

They require the FBI to destroy all approved gun purchaser records within 24 hours and prohibit the ATF from requiring gun dealers to submit their inventories.

The amendments have been attached to the Department of Justice's appropriations bills since 2003, according to the Giffords Law Center. The restrictions were loosened in 2008 and 2010 to allow more sharing of data with law enforcement agencies.

The Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986 prevents the federal government from maintaining a central database of firearms dealer records, the Giffords Law Center notes.

"ATF for example is barred from spending any money to digitalize records from out-of-business gun stores," said Avery Gardiner, the co-president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

When the ATF traces a gun sale, it begins by calling or emailing the gun store because there is no database to search. When a dealer goes out of business, those records are shipped to the ATF, which transfers them to non-searchable PDFs.

"It's incredibly inefficient but they've been basically instructed to use taxpayer dollars badly and inefficiently and slow down police efforts to solve crimes because of the concern that somehow a national registry of gun owners would lead to the government coming to confiscate everybody's weapons," Gardiner said.

—Stephen Stock contributed to this story