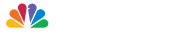

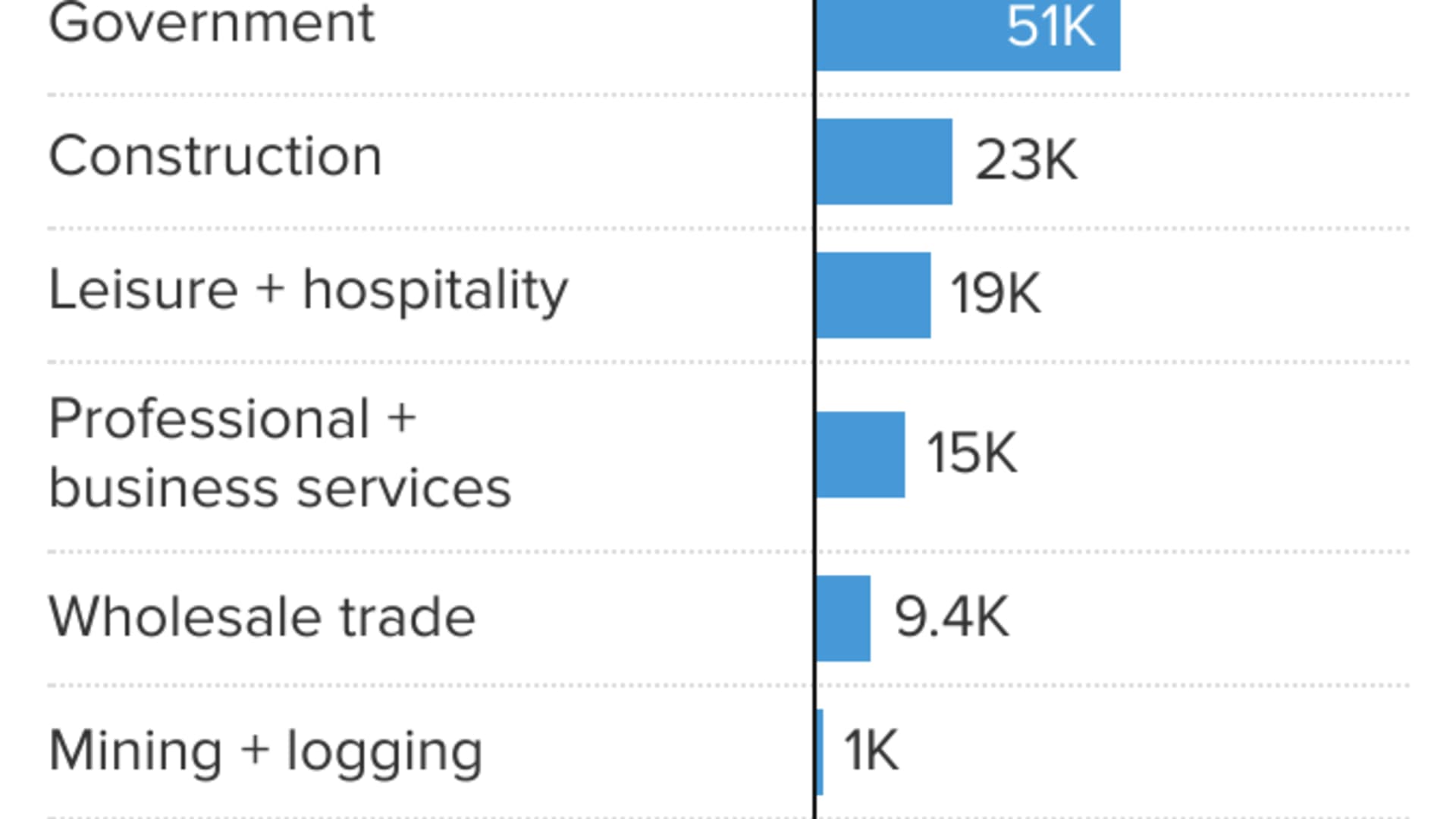

- U.S. job growth fell to 150,000 last month and unemployment rose to 3.9%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics' October jobs report.

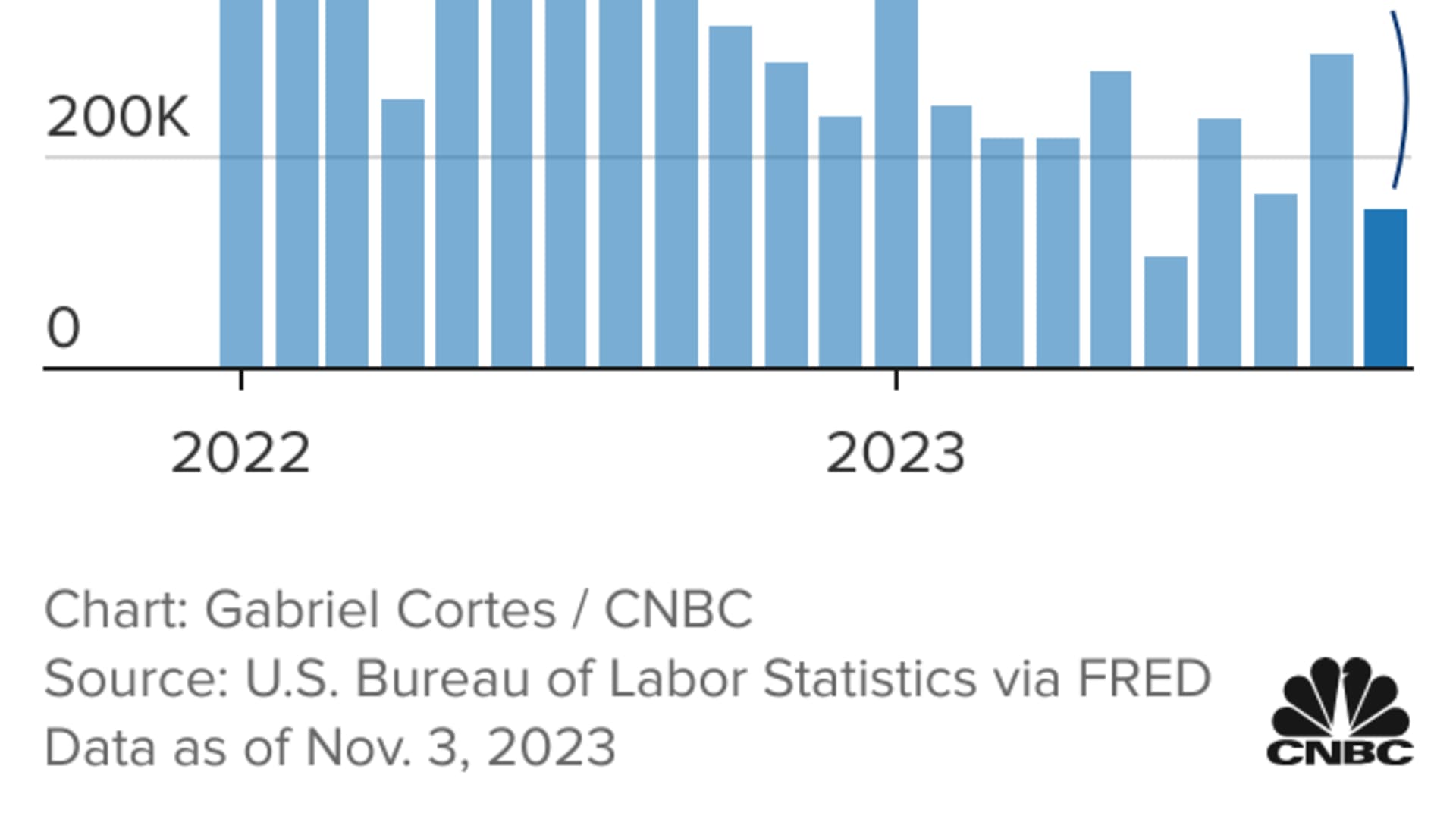

- Workers have lost some bargaining power and leverage from the historic levels seen in 2021 and 2022.

- Despite a broad cooldown, the labor market has been resilient in the face of headwinds and there doesn't seem cause for panic yet, economists said.

The job market continues to show signs of cooling, but alarm bells aren't ringing just yet, economists said.

The U.S. economy added 150,000 jobs in October, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Friday. That was less than expected and a "substantial slowdown" from the 260,000 monthly average so far in 2023, said Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter.

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

The unemployment rate rose to 3.9% in October, from 3.8% in September, the BLS said. Average hours worked declined slightly to 34.3 a week, the "very bottom end of the range" typical for good economic times, Pollak said.

"There's almost no exception in this report: Every indicator suggests a slowing, slackening labor market," she said.

Yet, there's cause for optimism. The job market has proven resilient in the face of economic headwinds and remains healthy in historical terms, economists said.

Money Report

"The days of explosive growth are gone, as the labor market shifts into healthier and more sustainable territory," said Noah Yosif, lead labor economist at UKG, a payroll and shift management company. "All indicators point to a continued lull in the immediate future. It's a slowdown, not a collapse."

Workers have lost some leverage

Recent labor trends mean workers and jobseekers have "lost considerable leverage" relative to the recent past, Pollak said.

For example, 18% of new hires reported getting a signing bonus in the third quarter, down sharply from 28% in Q2, according to a recent ZipRecruiter survey of new hires. Fifty-eight percent of new hires increased pay in their new roles, down from 65% the prior quarter.

"Even though historically [workers] are still doing well, I think many are comparing their lot to the way things were a year or two years ago, and they're feeling a pinch," Pollak said.

More from Personal Finance:

Why working longer is a bad retirement plan

Applying for too many jobs may keep you from getting hired

Union workers 'are catching up' on pay as labor organizing surges

Why the data isn't so gloomy

The overall jobs figure for October would have been higher — closer to 200,000 — absent strikes among autoworkers, actors and other union workers, economists said.

That would have been a "pretty spectacular number," said Aaron Terrazas, chief economist at Glassdoor, a career site.

"On the surface it was a weak number, but this was clearly clouded by all of the strikes that were happening mid-month," Terrazas said.

Indeed, there were nearly 50,000 workers on strike during the reference period the BLS uses to compile the jobs report, which was the largest number of workers on strike dating to 2004, Terrazas said.

Those strikes are now largely resolved.

The unemployment rate also remains below 4%, a key barometer.

"It tends to do great things in the labor market" when below 4%, Pollak said. "It tends to cause people to come off the sidelines, cause racial and gender wage gaps to narrow and force employers to improve working conditions and expand their talent pools."

However, the unemployment rate was 3.5% just a few months ago, in July, and it's rare to see that big an increase outside of recessions, Andrew Hunter, deputy chief U.S. economist at Capital Economics, said Friday in a research note.

That recent rise isn't yet "panic-worthy," but further increases "may begin to trip some recessionary alarm bells," said Nick Bunker, head of economic research at job site Indeed.

The rise in the unemployment rate may also just be a sign that the extremely hot labor market is loosening a bit, Bunker added.

The labor market cratered in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic amid mass job loss, a scale unseen since the Great Depression. However, it began heat up in 2021 and 2022 as the U.S. economy reopened and business' demand for workers spiked to a historic level.

Now, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates to cool the economy and tame inflation. That increase in borrowing costs for households and businesses is beginning to bite, Pollak said.

"While much in today's payroll report appeared to confirm a continued slowing in the labor markets, it's remarkable to witness how dynamic and resilient employment has been in the wake of the pandemic and inflationary shocks," said Rick Rieder, head of the global allocation investment unit at asset manager BlackRock.