Growing up, Tulsa native Bobby Eaton Jr. knew his grandfather Joseph was a respected member of the community in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. He knew Joseph owned a barber shop there — where Eaton's father and uncle were barbers — among other family-run small businesses.

What Eaton didn't know until he was an adult was that Joseph Eaton was a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre in Greenwood, and that he helped rebuild the area known as "Black Wall Street." As a kid, Eaton didn't even know the massacre had happened.

This May 31 to June 1 marks the 100th anniversary of the massacre, which occurred over two days in 1921 and saw an armed white mob descend upon Tulsa's Greenwood District. The area was one of the wealthiest Black communities in the U.S. and home to hundreds of Black-owned businesses, earning it its nickname. The violence that ensued killed as many as 300 of the city's Black residents, injured hundreds more and left 35 city blocks "in charred ruins."

Get a weekly recap of the latest San Francisco Bay Area housing news. Sign up for NBC Bay Area’s Housing Deconstructed newsletter.

It has been described as "the single worst incident of racial violence in American history," and much of the property and wealth the city's then-prosperous Black community had built up over decades was destroyed. A study commissioned by Oklahoma officials in 2001 determined that the massacre resulted in roughly $1.8 million in property damage in Greenwood, an amount that would equal nearly $27 million in today's dollars, based on inflation.

Today, Eaton, 66 owns a radio station and media company, Eaton Media Services, housed in the same building where his grandfather ran the barber shop for decades after the 1921 massacre.

As a Black business owner in Tulsa, Eaton feels he's both carrying on a family legacy while also continuing a tradition of Black entrepreneurship that goes back more than a century, to when the Greenwood District was teeming with Black-owned businesses.

Local

Now, Eaton hopes the massacre's centennial, and the increased national attention it brings to Tulsa, will help boost local efforts to revive the area even after the anniversary has passed.

"Everybody's talking Black Wall Street, for right now," Eaton tells CNBC Make It. "My thing is, can we restore and rebuild Black Wall Street? Can we get it back to where it was intended to be?"

A family of entrepreneurs

When the "Black Wall Street" massacre was perpetrated in 1921, Eaton's grandfather Joseph was a factory worker in his 20s. He joined the effort to rebuild the community in the aftermath, which included building the home where Eaton now lives and runs the radio station that broadcasts on KBOB 89.9 FM.

"He built this home that I occupy right now," Eaton says. "And next door to it was the barbershop … He went to work every day inside this barber shop. And as his children — my dad, Bobby Sr., and my Uncle Jerry — got older, they became barbers there as well."

Joseph also ran a nearby grocery store in the years after the massacre. But it was the barber shop that remained open for decades, passing down to the next generation of Eaton's family, and serving as an important meeting spot for the Black community in North Tulsa, Eaton says.

"That barber shop is where the civil rights movement from North Tulsa ... got started," he says, adding that his father and grandfather would meet with "all of these iconic black men in the community" when Eaton was a child in the 1960s to discuss racism and the Civil Rights movement, while planning local protests. (Eaton's father, Bobby Eaton Sr., was reportedly one of the first Black men arrested in Tulsa for protesting segregation laws in the 1960s.)

Last year, the Greenwood Rising History Center, which will open as part of the massacre's centennial, announced that an exhibit looking at members of the community who worked to rebuild Greenwood will feature a barber's chair from the shop to honor the family's history.

The massacre 'was never taught in schools'

In the 1970s, Eaton graduated from Tulsa's Booker T. Washington High School, which was one of the few buildings in Greenwood to remain standing after the massacre and even served as a headquarters for the Red Cross' relief efforts after the violent event. Founded in 1913, the school remains in operation and, today, the massacre is officially on the curriculum.

Eaton says he never discussed the massacre with his grandfather, whose generation of Black Tulsans he says mostly avoided the subject.

"It was never taught in the schools," Eaton says. "We did not know about that massacre coming up as children [and] the elders didn't really tell us."

Eaton is far from alone, of course, as historians have noted in recent years that the history of Black Wall Street and the massacre that occurred there have generally not been taught in U.S. schools over the past century, even in Oklahoma, where the racist incident only became an official part of the state's curriculum in February 2020.

Eaton says he can understand why many people of his grandfather's generation didn't want to rehash the massacre, noting that he knew some of the survivors worried that simply revisiting the tragic event could potentially stir up further violence.

"It was a traumatic event that took place," he says. "And then, as they were building up their communities and housing... they didn't want to talk about that. That was a hush-hush conversation."

Carrying on a tradition

Eaton became a musician, touring the world playing bass with the likes of Natalie Cole and Ike and Tina Turner. His music career took him away from Tulsa for decades, but he returned in 2016 and soon found himself looking to continue his family's legacy as a Black entrepreneur in Tulsa.

"I realized that being able to have a business and doing it, kind of, like the Black Wall Street way [as a Black business owner] was real important, and something that I really wanted to do," he says.

Not only did his father, grandfather and uncle cut hair at the family barber shop that operated through the "early 2000s," Eaton says, but other family members frequently ran other businesses in another open space in the same building, from a grocery store to a photo studio.

"It's been a lot of things throughout the years," says Eaton, whose brother, Dwight Eaton, is also a co-owner of a local coffee shop, the Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge, that's located in the heart of Greenwood.

Between his own family's history of running businesses in Tulsa and the history of Black Wall Street, Eaton now feels like he's carrying on multiple traditions as a Black business owner in the city.

He also sees the importance of operating a Black-owned media company in a community that once boasted the Black-owned Tulsa Star newspaper before it was destroyed during the massacre (a successor publication, called the Oklahoma Eagle still operates as a weekly newspaper) and is now also home to the Black-owned news website The Black Wall Street Times.

"Keeping that legacy going on [and] being able to spread information throughout the world about Black Tulsa is a good thing," says Eaton, who hosts his own program on his radio station four days a week, discussing current events and community issues. The station, which streams online as well, also features a weekly program created by a group of students from Tulsa's public schools, called the Juice Radio Show.

"[The station] is a platform where I feel like not only the community can connect to it, but the world can connect to it … It makes me feel good to know that I'm able to set that up for us."

Black Wall Street today... and tomorrow

Despite efforts to rebuild after the 1921 massacre, Greenwood looks a lot different now than it did a century ago.

Tulsa's "urban renewal" efforts in the 1960s and '70s razed much of the Greenwood District in favor of public works projects, including construction of a major highway in the 1960s that cut through the heart of the neighborhood.

"Today Black Wall Street is more of a Black Main Street," says a spokesperson for the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce. The chamber owns a stretch of about 10 buildings in Greenwood's business district on Greenwood Avenue, which was the heart of the original Black Wall Street. The spokesperson notes that the chamber's businesses "currently generate more than $4 million back in the Tulsa community" per year, and that the majority of those businesses "are Black-owned and operated."

Still, when asked to compare Greenwood today to its pre-1921 heyday, Sherry Gamble Smith, founder and CEO of the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce, a separate organization, says "there's no comparison to what the spirit of Black Wall Street was back... before the massacre."

In those days, she says, there were "a lot of thriving businesses" owned by and catering to the Black community. Today, though, the Black community does not own nearly as much property in Greenwood, making it more difficult for Black business owners to thrive in the area, says Gamble Smith, who herself runs an events business as well as a mentoring program for women and children.

Eaton agrees with Gamble Smith, saying that the key to restoring the spirit of Black Wall Street in Tulsa is for more Black entrepreneurs to have the means to own commercial property. He also stresses the importance of teaching younger generations about the history of Black Wall Street.

"Educate [the youth], tell them about the Black Wall Street," he says. "Let them have a sense of entrepreneurship about themselves, where maybe they want to grow up and open [a business]."

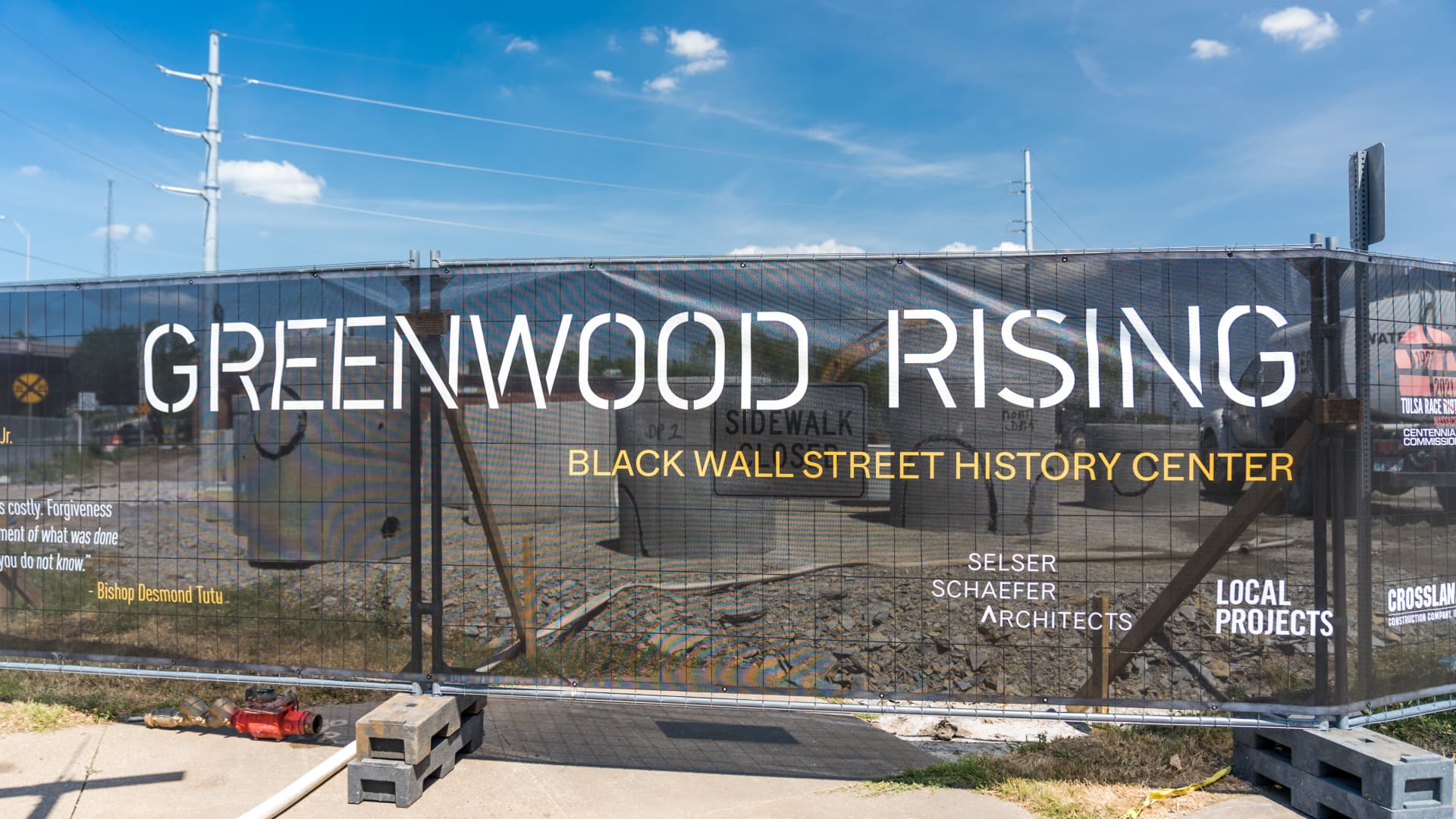

The centennial of the 1921 massacre should continue to shed light on the tragic and shameful event with a slate of commemorative events in Tulsa, from concerts to candlelight vigils, and the opening of the Greenwood Rising History Center. (President Joe Biden will visit the city to mark the centennial, while politician Stacey Abrams will give a speech and musician John Legend will perform.)

Eaton believes it's a good thing that the centennial will bring national attention to Tulsa and its traumatic history, as well as visitors and potentially significant tourism revenue for local businesses. But, he also wonders what, if anything, will really change once the centennial passes, the tourists go home, and the world's eyes turn somewhere else.

What will happen in Tulsa "after this centennial is over with and everybody goes back to their homes and houses and their cities?" he asks. "I'm still living here. I still deal with the trauma that took place here on Black Wall Street years ago."

Sign up now: Get smarter about your money and career with our weekly newsletter

Don't miss:

'Black Wall Street': The history of the wealthy Black community and the massacre perpetrated there